1. Setting the Stage . . . Framing

Key #1 has introduced you to two fundamental relationships between individual and society that help you understand how the entry point disconnect could have happened. Key #2 will now show you how to use this new perspective in your everyday life.

Key #2 focuses on framing—a basic and pervasive part of everyday life. Framing works something like the lens prescription in a pair of eyeglasses, which “frames” your perceptions of what’s going on around you. If you’re wondering why you don’t already know about framing—if it’s so pervasive—the answer is that we all focus overwhelmingly on what’s inside our frames, while overlooking the framing process itself.

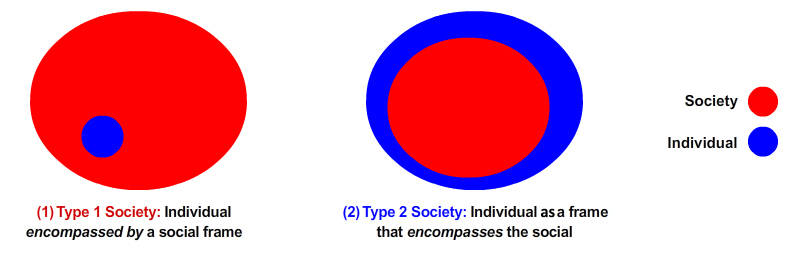

The effectiveness of frames arises from the fact that the perspectives they communicate are socially shared by others—in fact, so deeply shared that these perspectives are not seen as “our frames”, but as “the way things are”. Figure 6 below depicts the same relationship perspectives shown in Key #1 Figure 5—only this time they are shown as two different sets of framing perspectives. We think that one or the other of these perspectives frames the basic relationship of individual and society in all social communities.

Using these framing perspectives now we can now view the initial disconnect experienced by the newcomers and their hosts in Japan in a different light. If the initial disconnect is a clash of frames created by people moving between the two social types depicted below, then just being able to recognize these frames is the first step for anyone—including you—to begin to navigate beyond this disconnect. Moreover, you can do this no matter where you happen to be! This module will help you begin right now.

These two sets of expectations are portrayed in the figure below:

Figure 6. Two Framing Perspectives on Individual and Society

- Type 1 Societies prioritize society as frame, while the individual is viewed within the social frame. A social unit (such as the family, school, military unit, company, or nation) is foregrounded, while the individual is in the background, and viewed as encompassed in social ties. The Japanese ‘uchi’ perspective is one example of this focus. While it is beyond the scope of this course to elaborate all the societies which may fit into this type, we will begin by expanding Type 1 to other countries in Asia, for example, China, Korea, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam. As anthropologists, we also feel compelled to include indigenous Native American societies in both North and South America.

- Type 2 Societies prioritize the individual as frame, since the individual, in effect, encompasses the social frame. Put another way, society as the social and moral order is encompassed within the individual. This doesn’t mean that such societies lack social ties; but that the individual is foregrounded, while the social frame is in the background. This makes the individual (rather than a social unit) the focal point of social ties. This perspective on the individual is represented by European societies: for example, Great Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, France and Scandinavia. It also includes some societies established by colonization from the latter societies, for example, the U.S., Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The newcomers in this course all represent a variety of Type 2 societies. See newcomers and their societies.

We do not mean to imply that all Type 1 societies, or all Type 2 societies, are similar across the board—far from it. Nor do all segments of each society fit neatly into either Type 1 or Type 2 above. In a world with a complex history of colonization, migration, globalization, and complex patterns of immigration, the situation is anything but simple. Here we are suggesting that the two types above will give you a handle, as a useful starting point to establish: (1) the type of framing you are used to, and (2) the type of framing you are encountering in any new situation you happen to enter.

To see how this works for the newcomers just entering their situations in this program:

The newcomers are all from Type 2 societies and their entry situations are in a Type 1 society, Japan. This makes it entirely natural that the hosts should want their newcomers to pay attention to the social context surrounding them in ‘uchi’, and to try to fit themselves into their ‘uchi’ contexts, Yet it is equally natural that the newcomers should focus their attentions on their own individual concerns—of making the context fit them as ‘I’. The problem here is one of framing: the newcomers are viewing their entry situations through lenses that foreground the individual, while their Japanese hosts are framing the same situations through lenses that background the individual and foreground society.

The flash dynamic in 13.1 Figure 4 is crucial because it opens up a way for a newcomer like you to bridge the disconnect between hosts and newcomers depicted at the opening of this module. The key to the possibility that the newcomers can accommodate appropriately to their uchi surroundings is that the individually-oriented newcomers also possess a sense of society, even if this is backgrounded by them. By the same token the members of uchi also have a sense of being individuals, even though this is backgrounded by them as well, due to their perspective as individuals within uchi. The newcomers now have to learn to notice, and move to the foreground, much that they had assumed to be backgrounded. Things will go much better for their hosts as well, if they can begin to notice, and then try to do the same process in reverse. You can adapt this bridging process to other societies as well.

Key #1 helps you, the newcomer, to detect whether or not you face an initial disconnect in your new situation. If you do, then Key #2 shows you how to begin to navigate beyond this disconnect. You do this by beginning to notice how the ways of framing relationships between individual/society shown in Fig. 6 are turning up constantly in your daily life.

2. Tuning in to Framing in Daily Life

Key #2 introduces you to an intriguing puzzle: the perspectives on individual/society depicted in Types 1 and 2 above are embedded in many activities and forms that “frame” our everyday lives—but these are almost totally taken for granted—and unnoticed—by all of us. In this section we present a series of everyday examples to help you get attuned to the framing of individual versus society that is constantly going on in your everyday life. The key here is noticing the foregrounding/backgrounding that you have grown up with, and that no one thinks to tell you because this is “the way things naturally are”.

However, if you move to a society where foreground/background relationships are framed in the reverse way from your own (that is, from a Type 2 to Type 1 society, or vice versa), you will be confronted with a reoccurring lack of “fit”; a feeling that things are “our of synch”(or not being done the way you are used to) in everyday life. This begins with such basics as the order in which you write an address, or the formatting of name cards and job resumes. The newcomers you’ve followed through this program were all in this somewhat unnerving situation of lack of fit.

Now is your chance to become aware of how integral—and taken-for-granted—the process of framing is to your everyday life. The examples below should help you tune in to the ways you are used to framing vis-à-vis your own self and society, and how this could create a disconnect if you move to a society where this framing is reversed. The examples here include address forms, order of names, business card lay-outs, and birth registration. Formats for job resumes will be taken up in Module 13.3.

Everyday Framing Examples:

(1) Address Forms

Writing an address may seem straightforward. Yet addresses are not written the same way everywhere, and the order is significant. One of the address forms below will likely seem familiar to you; the other will not.

Click to color the examples below as: Type 1 society, Type 2 society.

(1) Can you identify the relationships between individual and society depicted in each address form? Which component is foregrounded and which is backgrounded?

(2) Does name order taken by itself also identify relationships between self and society?

Example 1: Tanaka Ken | Example 2: Ken Tanaka (given name, family name) |

(2) Business Card Lay-outs

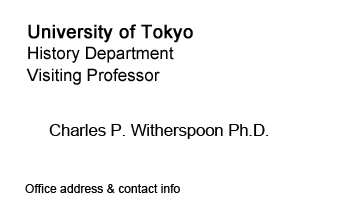

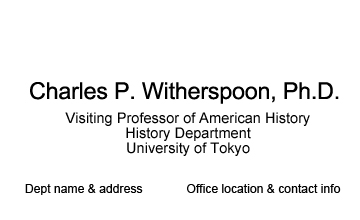

When Professor Witherspoon arrives at the University of Tokyo, he has a bilingual name card printed up for his guest affiliation in Japan, with one side in Japanese and the reverse side in English. His assistant helps him with the Japanese lay-out, and he realizes that this is different from the lay-out in English. The two versions are illustrated below:

Side 1: Japanese Language Format (translated)

Side 2: English Language Format

- These two lay-outs for Witherspoon’s name-card depict each of the two relationships between individual and organization outlined in Fig. 5. Which lay-out represents the individual inside the organization, and how is this accomplished by the ordering of the lay-out?

- Which organization focuses on the individual and how is this accomplished by the layout? What is the relationship of the organization to the individual in this lay-out?

- You have already seen how uchi involves a nesting series of groups within a larger collectivity for the newcomers in larger organizations—the school, company, dorm, university, and branch company office. Which of Witherspoon’s cards presents him within this nesting series of uchi, and how is this done?

- Does the lay-out foregrounding the individual also present a nesting series of groupings, and if so, how does the ordering of the nesting compare to that in 3. above?

These two lay-outs for Witherspoon’s name-card clearly depict each of the two relationships between individual and organization outlined above. The Japanese side presents the individual as inside the organization, (‘uchi’) while the English version represents the opposite relationship—the organization as subsumed within the individual (‘I’). Consequently,the relationship between individual and organization is reversed on the two sides of this card. Yet at the same time you can see that both individual and society are present on both sides of the card; it is the prioritization of one aspect encompassing the other that creates the difference in lay-outs.

(3) Birth Registration

The birth of a baby has social implications that ripple beyond the individual baby and its caregivers. Many countries require documentation of a baby’s birth as a basis for establishing the baby’s social identity and citizenship. Two common types of birth identification are pictured below:

*Keep in mind that not all societies have set up systems of birth documentation, and even among those that have, some don’t function in practice.

The birth certificate and family registry shown above are two very common forms of birth registration. Notice how the design of each form “frames” the baby’s relationship to society. Which form identifies a baby in a Type 1 society? Which baby is born into a Type 2 society? How does the design of the form tell you this? (Hint: Notice where each baby’s information appears on the form.)

Birth Registration Quiz

Repercussions exist for each type of birth registration shown above—some of which have wide-ranging or serious effects.

See if you can figure out which registration type creates each of the repercussions listed below. Drag the registry type you think best matches each numbered explanation into the box beside it.

Country Registration Quiz

Which form of birth registration do you think is used in each of the countries listed below? Match each country with the registry form you think it uses by dragging the appropriate form into the box beside it.

This quiz still tells us some important things, even though the geographical range of countries is limited:

- Type 1 societies appear to be common in Asia (including India, East and Southeast Asia). The individual in these societies is viewed within a social frame (as depicted in the family registry). Yet the social frame itself can differ considerably from society to society.

- Type 2 societies are common in Europe and North America. In these societies the individual is identified as the basic unit of society (as depicted in the birth certificate). The social frame is viewed as within the individual. The particular type of individual identified in the Type 2 perspective evolved only in one world area: Europe (especially northern Europe). It was then dispersed, for example, to North America (Canada and the U.S.) through European colonization.

- Indigenous societies, including Native Americans in North and South America, Inuit in polar regions, !Kung Bushmen in the Kalahari, Ainu in Japan; tribal societies in China, Burma, Indonesia, and other Asian societies, (to name a few) have also been Type 1 societies.

- This is a bit simplified, but we will orient you further in the final module.

Key #2 orients you to different (and opposite) ways of representing everyday transactions that you may encounter when you move abroad. But it is crucial for you to realize that behind these seemingly minor formatting differences in everyday life are nothing less than the two opposing ways of framing relationships between individual and society that are the basis of Key #1.